The MOdern ONI

The traditional oni was popularized in medieval Japan and persisted throughout the age. However, by the time of early modern Japan (1600-1867), the oni had retreated somewhat in the Japanese popular conscience. No longer did oni threaten the authority of the central courts, nor did the imperial councils concern themselves as much with worries about oni. However, the idea of oni persisted quite strongly in the minds of everyday people. In art, oni flourished. The early modern period marks the slow recession of oni from immediate personal relevance to being regarded as more fictitious characters from legends and the arts. In general, the early modern era saw the "de-demonization" of the oni (Reider, "Japanese Demon Lore" 92).

Noriko Reider, an expert in oni at Utah State University and author of Japanese Demon Lore: Oni, writes that "By the middle of the seventeenth century, Yamaoka Genrin had already expressed that Shuten Dõji [the fabled chieftain of all oni] was an evil human rather than a supernatural creature called oni" ("Japanese Demon Lore" 92). The trend of depicting oni in less serious and less frightening ways was accelerated by the forces of commercialism. Oni slowly became marketable objects that were featured in souvenirs, popular literature, and plays. Books about oni were sold at sideshows at carnivals. Starting in the late 18th century, belief in oni in urban areas decreased, probably due to urbanites' access to literature and art that portrayed oni in less-than-serious fashion. Urban dwellers thought of oni as monsters that lived far away among the wilderness but posed little threat to their day-to-day lives.

Because the oni found a place in art and culture, they survived, but only as imaginary beings. In the early twentieth century, Japan's eagerness to appear modern and advanced to the western world had several curious effects on superstition in Japan. Most superstition was looked down upon and discouraged because it was seen as uneducated and unworldly. However, the emperor did encourage some beliefs in the supernatural (namely, the belief that he himself was a manifest deity in order to cement his power), and the use of the word oni came back into play to label those who had different customs that were outside of the emperor's control (Reider 104). Quite interestingly, oni was used by the Japanese during World War II to characterize the Americans, British, Russians, and Chinese, all of which were seen as enemies of Japan.

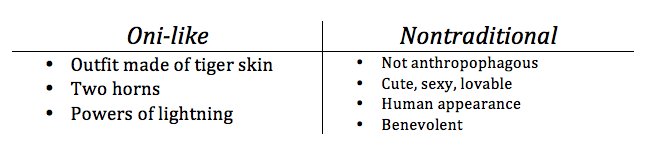

Post-WWII, manga and anime took hold in Japan. Both became prominent aspects of the country's pop culture. The oni that exist in today's Japanese culture are more varied than they have ever been, in large part due to their depictions in anime and manga. One example that Reider highlights in her book Japanese Demon Lore is that of the character Lum from the anime series Urusei Yatsura. Lum, who Reider describes as a "sexy, lovable ogress" (155), defies many of the traditional definitions of oni. She is a technologically advanced oni-alien hybrid that comes to earth and falls in love with the main character Moroboshi Ataru. He characteristics of Lum are summarized in the table below.

Noriko Reider, an expert in oni at Utah State University and author of Japanese Demon Lore: Oni, writes that "By the middle of the seventeenth century, Yamaoka Genrin had already expressed that Shuten Dõji [the fabled chieftain of all oni] was an evil human rather than a supernatural creature called oni" ("Japanese Demon Lore" 92). The trend of depicting oni in less serious and less frightening ways was accelerated by the forces of commercialism. Oni slowly became marketable objects that were featured in souvenirs, popular literature, and plays. Books about oni were sold at sideshows at carnivals. Starting in the late 18th century, belief in oni in urban areas decreased, probably due to urbanites' access to literature and art that portrayed oni in less-than-serious fashion. Urban dwellers thought of oni as monsters that lived far away among the wilderness but posed little threat to their day-to-day lives.

Because the oni found a place in art and culture, they survived, but only as imaginary beings. In the early twentieth century, Japan's eagerness to appear modern and advanced to the western world had several curious effects on superstition in Japan. Most superstition was looked down upon and discouraged because it was seen as uneducated and unworldly. However, the emperor did encourage some beliefs in the supernatural (namely, the belief that he himself was a manifest deity in order to cement his power), and the use of the word oni came back into play to label those who had different customs that were outside of the emperor's control (Reider 104). Quite interestingly, oni was used by the Japanese during World War II to characterize the Americans, British, Russians, and Chinese, all of which were seen as enemies of Japan.

Post-WWII, manga and anime took hold in Japan. Both became prominent aspects of the country's pop culture. The oni that exist in today's Japanese culture are more varied than they have ever been, in large part due to their depictions in anime and manga. One example that Reider highlights in her book Japanese Demon Lore is that of the character Lum from the anime series Urusei Yatsura. Lum, who Reider describes as a "sexy, lovable ogress" (155), defies many of the traditional definitions of oni. She is a technologically advanced oni-alien hybrid that comes to earth and falls in love with the main character Moroboshi Ataru. He characteristics of Lum are summarized in the table below.

As the table shows, Lum retains very little of the true oni nature of medieval and early modern Japan. She represents the latest development in the long trend of commercialization of oni myth. As Reider remarks, "this trend has seemingly reached its apotheosis in current Japanese culture. Thus, oni now flourish in Japanese people's nostalgia as well as futuristic imaginations" (120).

Considering all of this information in regard to the modern popularity of traditional oni tattoo design, one can see that those with oni tattoos still find the traditional form relevant. While fun modern takes on the oni might captivate the imagination, they are all derivatives of the iconic design that has been intertwined into Japanese history (and therefore identity). To owners of the oni mask tattoo, it is a timeless design-- no matter what the interpretation-- modern or ancient-- the oni motif has so thoroughly ingrained itself into the Japanese culture so as to be ever-relevant.

Considering all of this information in regard to the modern popularity of traditional oni tattoo design, one can see that those with oni tattoos still find the traditional form relevant. While fun modern takes on the oni might captivate the imagination, they are all derivatives of the iconic design that has been intertwined into Japanese history (and therefore identity). To owners of the oni mask tattoo, it is a timeless design-- no matter what the interpretation-- modern or ancient-- the oni motif has so thoroughly ingrained itself into the Japanese culture so as to be ever-relevant.