Connecting Themes

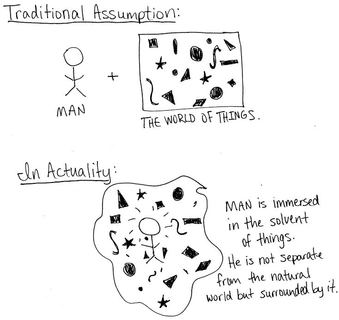

Fig. 1: Challenging the traditional view. Original graphic.

Fig. 1: Challenging the traditional view. Original graphic.

Historically, man has thought of himself as being separate from the rest of the natural world. Indeed, there are reasons for thinking so—humans have abilities of cognition and organization that far surpass most natural species. The power of creativity, man’s most remarkable attribute, seems to set him apart from the rest of the natural world. However, this traditional way of thinking is deeply flawed. Throughout the course of 10 Things: An Archaeology of Design, we have examined relevant artifacts that, when taken collectively, challenge the notion that man is separate from the natural world. After thoroughly studying our “Eleventh Thing,” the Japanese oni mask tattoo, we have formulated an alternate viewpoint. Rather than consider man apart from nature, we assert that man is totally immersed within the natural world, just like all other material things. He simultaneously influences the natural world and feels its influence. However, man’s intellect and creative desires allow him to interact with nature in unique ways. Man alone has the ability to selectively form interfaces with objects in the material world for virtually unlimited purposes.

This unique ability means that man has always been a “designer” of sorts; he uses his body to mold objects from the natural world into useful tools. Man’s ability to design his own tools has come to define humans as a “cyborg” species composed of the body and many inanimate add-ons or tools. Often, the tools man makes are practical: a flint hand axe, a hammer, an automobile, or a bulldozer are all examples of practical tools created by man. Other times, man creates tools to fulfill non-utilitarian desires—from this process springs all art. In art, man assembles materials from the natural world into symbolically meaningful or aesthetically beautiful expression of thought and sentiment.

This unique ability means that man has always been a “designer” of sorts; he uses his body to mold objects from the natural world into useful tools. Man’s ability to design his own tools has come to define humans as a “cyborg” species composed of the body and many inanimate add-ons or tools. Often, the tools man makes are practical: a flint hand axe, a hammer, an automobile, or a bulldozer are all examples of practical tools created by man. Other times, man creates tools to fulfill non-utilitarian desires—from this process springs all art. In art, man assembles materials from the natural world into symbolically meaningful or aesthetically beautiful expression of thought and sentiment.

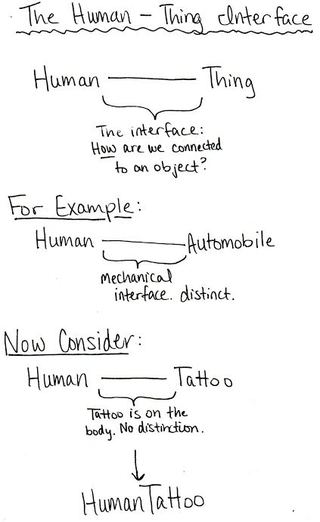

Fig. 2: The Human-Thing Interface. Original graphic.

Fig. 2: The Human-Thing Interface. Original graphic.

Among the different art forms, tattoos are perhaps the most illuminating to the idea of man as a “cyborg” race. This is because tattoos blur the line between man and thing more than any other tool. Tattoos are intimately connected to their owners for two main reasons. Firstly, they are tools of expression rather than tools of utility. Secondly, because they are permanently imbued into the body, tattoos blur the distinction between man and tool.

Contrary to popular belief, the ability to make tools does not distinguish humans from other species. Jane Goodall first observed that chimpanzees make and use tools in 1960. Furthermore, biologists have discovered that in addition to many primate species, some species of birds, elephants, and otters have the ability to use tools. However, humans are unique in that they use art as a tool of expression. No other species has the ability to create deeply symbolic art pieces as a means of self-expression, nor does any other species appear to have the cognitive ability to think abstractly enough to create art. Therefore, the tattoo is distinctly human and thus it helps define us as a species.

Secondly, tattoos blur the line between man and tool. As figure 2 illustrates, the interface between most human-thing systems is quite distinct. For example, an automobile is an example of a tool for which the distinction is clear. It is a solid object distinct from the body that a human uses by physically manipulating it (moving the steering wheel). A tattoo, however, is much more intimately connected to its “user.” The tattoo is imbued into the very body of a person; the interface between human and thing dissolves and they become one. This is illustrated in figure 2. The tattoo, then, is a perfect representative example of the “cyborg” tendency of humans to incorporate things from the external world into their own bodies.

Few cultures have been as influenced by the tattoo as Japan. The traditional oni mask tattoo of Japan is a fascinating case study of the notion that man is a “cyborg” composite of himself and the things from the material world. The aesthetics and symbolism of the oni imbue the design with great cultural significance to the Japanese. Thus, any Japanese that chooses to get an oni tattoo is making a conscious design choice. They are choosing to receive a permanent symbol of the culture that they are part of. This choice goes very deep—beyond the desire to modify one’s environment, there is the desire to modify one’s own body. Considering this along with the fact that tattoos are painful and often frowned upon in society, it is clear that those with oni mask tattoos were very serious about getting them. This shows that tattoos are an important object in Japanese society—they were born out of Japanese culture, they have survived the ages, and they continue to influence culture in Japan. Thus, they truly represent how a “thing” can be created by a culture and then in turn influence that culture.

Contrary to popular belief, the ability to make tools does not distinguish humans from other species. Jane Goodall first observed that chimpanzees make and use tools in 1960. Furthermore, biologists have discovered that in addition to many primate species, some species of birds, elephants, and otters have the ability to use tools. However, humans are unique in that they use art as a tool of expression. No other species has the ability to create deeply symbolic art pieces as a means of self-expression, nor does any other species appear to have the cognitive ability to think abstractly enough to create art. Therefore, the tattoo is distinctly human and thus it helps define us as a species.

Secondly, tattoos blur the line between man and tool. As figure 2 illustrates, the interface between most human-thing systems is quite distinct. For example, an automobile is an example of a tool for which the distinction is clear. It is a solid object distinct from the body that a human uses by physically manipulating it (moving the steering wheel). A tattoo, however, is much more intimately connected to its “user.” The tattoo is imbued into the very body of a person; the interface between human and thing dissolves and they become one. This is illustrated in figure 2. The tattoo, then, is a perfect representative example of the “cyborg” tendency of humans to incorporate things from the external world into their own bodies.

Few cultures have been as influenced by the tattoo as Japan. The traditional oni mask tattoo of Japan is a fascinating case study of the notion that man is a “cyborg” composite of himself and the things from the material world. The aesthetics and symbolism of the oni imbue the design with great cultural significance to the Japanese. Thus, any Japanese that chooses to get an oni tattoo is making a conscious design choice. They are choosing to receive a permanent symbol of the culture that they are part of. This choice goes very deep—beyond the desire to modify one’s environment, there is the desire to modify one’s own body. Considering this along with the fact that tattoos are painful and often frowned upon in society, it is clear that those with oni mask tattoos were very serious about getting them. This shows that tattoos are an important object in Japanese society—they were born out of Japanese culture, they have survived the ages, and they continue to influence culture in Japan. Thus, they truly represent how a “thing” can be created by a culture and then in turn influence that culture.