Oni Lore: HOw Legend Influences Design

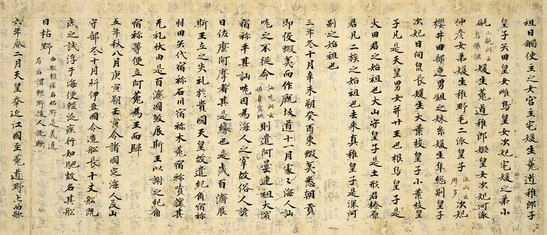

Above: pages from the Nihon Shiki, Japan's second-oldest chronicle

Above: pages from the Nihon Shiki, Japan's second-oldest chronicle

The full body tattoos with design influence originating from the prints of the heroes. This was the beginning of the new style of Japanese tattooing known as horimono, which is based on the Japanese verb horu, meaning to engrave, puncture, or incise, which is used for other art forms such as carving, engraving, and sculpting. The Japanese used the term irezumi, meaning "to insert ink" but this word is commonly associated with punishment and disapproval of the practice. Full body tattoos are therefore more often called horimono because the word is associated with positivity and artistry.

Japanese horimono, according to Joy Hendry, a professor with a focus in social anthropology, is the most aesthetically developed style of tattooing and typically covers the body from elbows to the core, down the back and front reaching all the way to the knees. Since the tattoos were illegal in Japan until 1945, people got these elaborate tattoos of heroes, religious figures, and flowers as the focal points with smaller designs embedded within them, and then covered the elaborate designs with clothing. Society rebelled against the ban, which Hendry describes as a form of play, through these acts of body decoration or they chose to sew colorful linings into their coats. Both tattoos and colorful linings were a status symbol that indicated wealth which is why tattooing continued to persist even during the prohibition. Hendry further tells us that these tattoos are only revealed during times of "play" through the club culture where tattoos come to life under ultra-violet light.

After 1945, when the tattoo prohibition ended, tattooing became once again prominent among the Yakuza, or Japanese mafia gangsters. Society’s image of these gangsters, Hendry says, “ Was partly of terror, partly romantic, through their portrayal in films and television dramas.” Hendry further describes that these gangsters were operating in the realm of play through gambling, prostitution, and drugs. oni of Japanese legend are viewed by most as grotesque, hideous creatures. Indeed, with their sharp teeth, unkempt hair, multicolored skin, and devilish horns, the oni would surely inspire terror in any mortal who may witness them. However, the “traditional” depiction of oni is not well defined but actually quite ambiguous; depending on the source, context, and time period, oni have been depicted as male, female, or shape-shifting demons. They vary in skin color, size, and number of horns. Also, the character of oni is rather loosely defined; depending on the story and region of Japan, oni may be wholly evil or both good and evil. The variance among visual characteristics in oni tattoo designs is due to the large variance in depiction of oni in Japanese lore. Going through time, we can see the origins and evolution of oni characteristics in Japanese mythology.

Early Tales of Gods and Demons

In the ninth month of 711 CE, the Empress Gemmei tasked the compiler Ôno Yasumaro to record Japan’s Ancient Myth. The resulting collection of myths, called the Kojiki, is Japan’s oldest extant chronicle. Although no oni are explicitly mentioned in the Kojiki, the chronicle does include tales of huge, incredibly powerful kami (gods) that created the four regions of Japan. The kami display many characteristics and behaviors that are similar to oni, and in this way they may be seen as precursors to oni in mythology. Like the oni, the kami were known chiefly for their destructive powers and opposition to order (Toji). Chaos and destruction almost always accompanied the kami wherever they went. The kami interacted both amongst themselves and with the mortals. One kami, Susa-no-o-no-mikoto, is particularly relevant to later oni depictions because of his victory over the evil Yamata-no-orochi, who was known for terrorizing mortals (Toji). Because of this legend, Susa-no-o-no-mikoto is not viewed as wholly evil, an important development for the later, more complex depictions of oni as neither good nor evil.

Later, in the year 720 CE, the Nihon Shiki was written. The Nihon Shiki, like the Kojiki, recorded early Japanese history and creation myths (Brown). Notably, the Nihon Shiki contains the earliest mentions of oni. However, the oni of the Nihon Shiki are quite different from the oni most people think of today, which were popularized in medieval Japanese texts. The first account of oni in the Nihon Shiki describes a sub-human being that lives on a small boat and subsists on the fish he catches. Later in the text, the term “oni” is used almost as a substitute for “stranger” or “outsider” (Toji). Thus, the word “oni” describes an outsider living at the fringes of society. While less terrifying than most depictions, this account established oni as beings who inhabit the natural world, yet are not quite human. In contrast to the kami, which are wholly supernatural, the oni are perhaps more “real” to the Japanese because of their connections to the natural world. This blurring of the distinction between god and human directly manifests itself in oni mask design, where oni appear as human-like creatures. The humanoid form of the oni is a result of early legends that cast oni as human-like beings imbued with a degree of supernatural otherness.

Notions of the physical appearance of Oni are informed by popular legends

Legends of oni in Japanese folklore describe their appearance and habits. Today, almost all depictions of oni (and particularly oni mask tattoos) feature a snarling face with large teeth and sharp carnivorous fangs. This most salient feature of the oni is rooted in legend; oni use their sharp teeth to eat human flesh. For example, one early story taken from the Nihon ryoiki (ca. 823) features a terrible cannibalistic oni (Reider 136). The story, titled “On a Woman Devoured by an Oni,” tells the tale of a beautiful maiden who will accept no suitor. One day, a mysterious suitor sends her many splendid and extravagant gifts, and she is very pleased so she agrees to marry him. On her wedding night, her parents hear her having pain and think that she is only making noise because she is not used to sex. However, they enter her bedroom the next morning to find that most of her body had been devoured by the oni. Here, the oni first appeared as a human male, but later shape-shifted into its true terrible form. The ability of oni to appear as humans further solidifies their humanoid design and makes them even more frightening because they may trick unsuspecting victims into trusting them.

Eerily Human: Supernatural Oni in the Natural World

As mentioned before, much of the intrigue and terror they oni inspire is related to their distinctly humanoid design. Their appearance seems to suggest a connection to humans. Interestingly, this connection is made concrete by traditional stories that tell of ordinary humans transforming into oni. In one story from the Konjaku monogatarishu (ca. 1212), the emperor summons a holy mountain ascetic to heal his ailing consort (Reider 138). The ascetic, however, falls deeply in love with the consort and is discovered by the king and sentenced to prison. In prison, the ascetic vows to come back as an oni. Later, he starves himself to death and is transformed into a powerful oni. The oni then returns to the emperor’s consort and “realizes his carnal desire” with the consort in public, while the emperor is powerless to stop him (Reider 138). The oni of this story is the demonic personification of intense carnal desire—literally a passion brought to life. In other stories, oni are personified hatred or rage. By their ability to be born of intense human passion, the oni show that they are rather human after all. In this way, the mythology provides a wise metaphor that warns against letting one’s “demons” (vices) get out of control, lest they take on a grotesque life of their own. Any emotion (whether it be anger, lust, courage, pride, et cetera) that a person feels with extreme intensity may be brought to life in an oni demon. So, the oni motif in art and tattoo design is often representative of personified passions and intensity of emotion.

Japanese horimono, according to Joy Hendry, a professor with a focus in social anthropology, is the most aesthetically developed style of tattooing and typically covers the body from elbows to the core, down the back and front reaching all the way to the knees. Since the tattoos were illegal in Japan until 1945, people got these elaborate tattoos of heroes, religious figures, and flowers as the focal points with smaller designs embedded within them, and then covered the elaborate designs with clothing. Society rebelled against the ban, which Hendry describes as a form of play, through these acts of body decoration or they chose to sew colorful linings into their coats. Both tattoos and colorful linings were a status symbol that indicated wealth which is why tattooing continued to persist even during the prohibition. Hendry further tells us that these tattoos are only revealed during times of "play" through the club culture where tattoos come to life under ultra-violet light.

After 1945, when the tattoo prohibition ended, tattooing became once again prominent among the Yakuza, or Japanese mafia gangsters. Society’s image of these gangsters, Hendry says, “ Was partly of terror, partly romantic, through their portrayal in films and television dramas.” Hendry further describes that these gangsters were operating in the realm of play through gambling, prostitution, and drugs. oni of Japanese legend are viewed by most as grotesque, hideous creatures. Indeed, with their sharp teeth, unkempt hair, multicolored skin, and devilish horns, the oni would surely inspire terror in any mortal who may witness them. However, the “traditional” depiction of oni is not well defined but actually quite ambiguous; depending on the source, context, and time period, oni have been depicted as male, female, or shape-shifting demons. They vary in skin color, size, and number of horns. Also, the character of oni is rather loosely defined; depending on the story and region of Japan, oni may be wholly evil or both good and evil. The variance among visual characteristics in oni tattoo designs is due to the large variance in depiction of oni in Japanese lore. Going through time, we can see the origins and evolution of oni characteristics in Japanese mythology.

Early Tales of Gods and Demons

In the ninth month of 711 CE, the Empress Gemmei tasked the compiler Ôno Yasumaro to record Japan’s Ancient Myth. The resulting collection of myths, called the Kojiki, is Japan’s oldest extant chronicle. Although no oni are explicitly mentioned in the Kojiki, the chronicle does include tales of huge, incredibly powerful kami (gods) that created the four regions of Japan. The kami display many characteristics and behaviors that are similar to oni, and in this way they may be seen as precursors to oni in mythology. Like the oni, the kami were known chiefly for their destructive powers and opposition to order (Toji). Chaos and destruction almost always accompanied the kami wherever they went. The kami interacted both amongst themselves and with the mortals. One kami, Susa-no-o-no-mikoto, is particularly relevant to later oni depictions because of his victory over the evil Yamata-no-orochi, who was known for terrorizing mortals (Toji). Because of this legend, Susa-no-o-no-mikoto is not viewed as wholly evil, an important development for the later, more complex depictions of oni as neither good nor evil.

Later, in the year 720 CE, the Nihon Shiki was written. The Nihon Shiki, like the Kojiki, recorded early Japanese history and creation myths (Brown). Notably, the Nihon Shiki contains the earliest mentions of oni. However, the oni of the Nihon Shiki are quite different from the oni most people think of today, which were popularized in medieval Japanese texts. The first account of oni in the Nihon Shiki describes a sub-human being that lives on a small boat and subsists on the fish he catches. Later in the text, the term “oni” is used almost as a substitute for “stranger” or “outsider” (Toji). Thus, the word “oni” describes an outsider living at the fringes of society. While less terrifying than most depictions, this account established oni as beings who inhabit the natural world, yet are not quite human. In contrast to the kami, which are wholly supernatural, the oni are perhaps more “real” to the Japanese because of their connections to the natural world. This blurring of the distinction between god and human directly manifests itself in oni mask design, where oni appear as human-like creatures. The humanoid form of the oni is a result of early legends that cast oni as human-like beings imbued with a degree of supernatural otherness.

Notions of the physical appearance of Oni are informed by popular legends

Legends of oni in Japanese folklore describe their appearance and habits. Today, almost all depictions of oni (and particularly oni mask tattoos) feature a snarling face with large teeth and sharp carnivorous fangs. This most salient feature of the oni is rooted in legend; oni use their sharp teeth to eat human flesh. For example, one early story taken from the Nihon ryoiki (ca. 823) features a terrible cannibalistic oni (Reider 136). The story, titled “On a Woman Devoured by an Oni,” tells the tale of a beautiful maiden who will accept no suitor. One day, a mysterious suitor sends her many splendid and extravagant gifts, and she is very pleased so she agrees to marry him. On her wedding night, her parents hear her having pain and think that she is only making noise because she is not used to sex. However, they enter her bedroom the next morning to find that most of her body had been devoured by the oni. Here, the oni first appeared as a human male, but later shape-shifted into its true terrible form. The ability of oni to appear as humans further solidifies their humanoid design and makes them even more frightening because they may trick unsuspecting victims into trusting them.

Eerily Human: Supernatural Oni in the Natural World

As mentioned before, much of the intrigue and terror they oni inspire is related to their distinctly humanoid design. Their appearance seems to suggest a connection to humans. Interestingly, this connection is made concrete by traditional stories that tell of ordinary humans transforming into oni. In one story from the Konjaku monogatarishu (ca. 1212), the emperor summons a holy mountain ascetic to heal his ailing consort (Reider 138). The ascetic, however, falls deeply in love with the consort and is discovered by the king and sentenced to prison. In prison, the ascetic vows to come back as an oni. Later, he starves himself to death and is transformed into a powerful oni. The oni then returns to the emperor’s consort and “realizes his carnal desire” with the consort in public, while the emperor is powerless to stop him (Reider 138). The oni of this story is the demonic personification of intense carnal desire—literally a passion brought to life. In other stories, oni are personified hatred or rage. By their ability to be born of intense human passion, the oni show that they are rather human after all. In this way, the mythology provides a wise metaphor that warns against letting one’s “demons” (vices) get out of control, lest they take on a grotesque life of their own. Any emotion (whether it be anger, lust, courage, pride, et cetera) that a person feels with extreme intensity may be brought to life in an oni demon. So, the oni motif in art and tattoo design is often representative of personified passions and intensity of emotion.